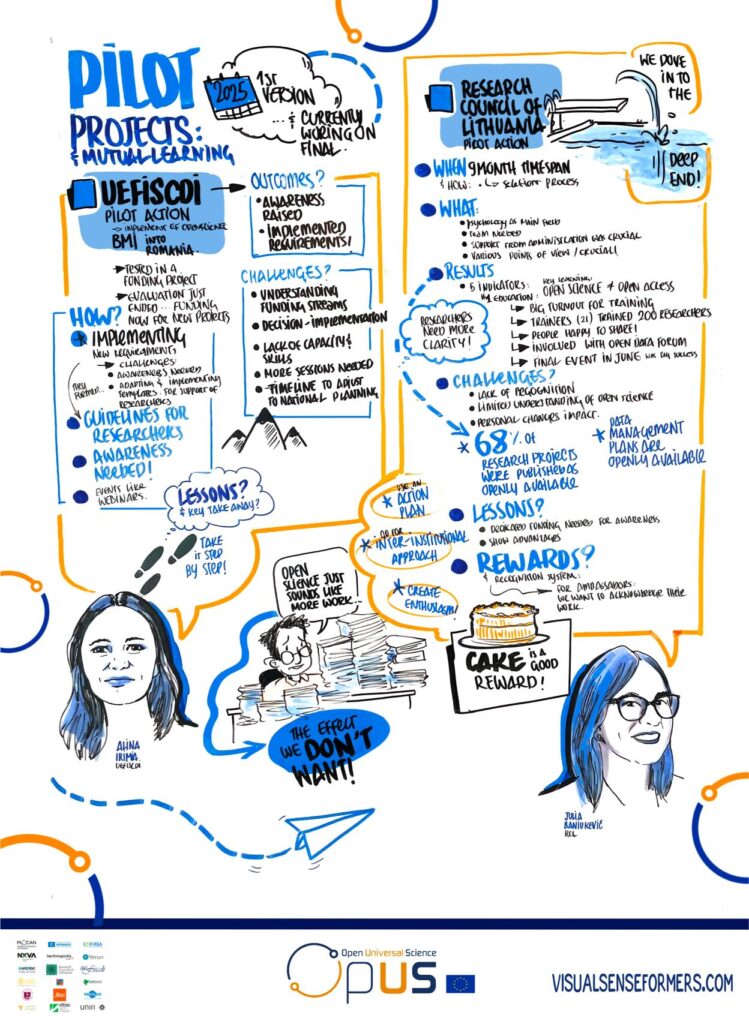

Research Council of Lithuania (RCL) Pilot Action presented at the Final Conference

Research Council of Lithuania (RCL) Pilot Action presented at the Final Conference https://opusproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Julija-1-1024x683.jpg 1024 683 Open and Universal Science (OPUS) Project Open and Universal Science (OPUS) Project https://opusproject.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Julija-1-1024x683.jpgJulija Baniukevic from the Research Council of Lithuania (RCL) presented an exemplary community-driven approach to Open Science implementation at the OPUS (Open and Universal Science) Final Conference held at the UNESCO International Institute of Educational Planning (IIEP) in Paris on 9-10 July 2025, marking the culmination of a transformative journey to reform research assessment systems across Europe and beyond.

Dr Baniukevic, who serves as OPUS Project coordinator in Lithuania, has extensive experience in bionanotechnology research, policy advocacy, and European science cooperation.

The Lithuanian pilot implemented a comprehensive training programme over nine months, reaching 21 principal investigators from various research fields who subsequently trained 211 researchers in their teams. The programme achieved remarkable engagement levels, with 91% attending on-site training and 20 out of 21 trainers conducting sessions for their teams. Participants showed strong commitment, with 68.2% of research outputs made openly accessible and 82.6% of participants initiating open science dialogues in their institutions.

Julija Baniukevic (RCL): Why did we achieve such good results in just nine months?

When we were reorganising our approach, we had only nine months to achieve our goals, so we had to consider carefully at which level to act. We decided to focus on principal investigators (PIs) and selected one call with 136 winners. All were invited to participate; 46 expressed interest and attended the introductory session in September. Out of these, 26 began the programme, 23 continued throughout the year, and 19 completed the full nine-month programme and received certificates.

I was pleased that six Lithuanian institutions participated: four universities and two research institutes. We covered almost all research fields, with psychology representing about 18% of the participants, which was particularly interesting, though other fields were also well represented.

Recognising that you cannot achieve anything alone, I formed a team with support from our vice-chair, Vaiva Prudokinia, and established an Advisory Board within the Research Council. I was joined by three colleagues, Justina, Agla, and Girinta, from different departments: the Research and Business Cooperation Unit, the Researcher Support and EU Investment Unit, and the Research and Higher Education Policy Analysis Unit. Having diverse perspectives was crucial, and without these colleagues, our achievements would not have been possible.

Let me turn to our results. Our researchers, along with others trained during the OPUS pilot, participated in a nine-month programme. We selected five indicators: two in education, two in research, and one in valorisation.

Starting with education, we identified a common misunderstanding among researchers, who often equate open science solely with open access. We wanted to broaden their understanding, so we began with courses on open science. Initially, I was unsure whether these would be well received, but 91% of participants attended the on-site training, which was a pleasant surprise and made me proud of our researchers.

Over two days, we covered many topics, which was a great success and helped us build stronger connections with participants. After the initial training, participants received certificates as trainers. For the next four months, these trainers delivered training sessions to their own teams and laboratories. In total, 21 PIs trained 211 researchers, sharing knowledge and experiences. Only one person did not deliver the training, as she had not completed the full programme.

This group of researchers were enthusiastic about sharing their knowledge. Three trainers even organised a full-day conference on open science, which attracted 70 participants. We also involved one trainer in the Open Data Forum, organised by my colleague Girinta, where she represented both the OPUS project and open science in panel discussions. At our final event in June, eight cohort members shared their experiences, initiatives, and perspectives on open science, including the challenges they encountered.

These activities were a significant success, but we also identified some challenges. For example, some researchers mentioned a lack of compensation, so we are considering mechanisms for micro-rewards. There is also a lack of institutional recognition for public engagement activities, which we hope will improve. Limited understanding of the open science concept was evident, but over the nine months of our ambassador programme, we saw that researchers are eager to develop new skills and adapt open science practices to their own systems.

We also observed that personnel changes can impact pilot implementation, which is something to consider in future projects.

Turning to research indicators, we monitored the number of openly available publications. We had many discussions about what constitutes open access, including whether embargoes should be counted. In total, the cohort produced 85 publications, of which 58 (68%) were openly available. Interestingly, about 42% of researchers published exclusively in open access, while others published more than half of their work openly, though some published less. This is an interesting result, even if our sample size is small.

The fifth indicator was openly available data management plans (DMPs). We prepared recommendations for researchers, which will be added to our website. In collaboration with the Ombudsperson and her team, especially Reda, we analysed what needs improvement and how to enhance our management plans. All ten researchers agreed to make their DMPs openly available, and by the end of July, these will be published on the Research Council’s website in a dedicated section.

However, we still face issues. For example, when researchers submit proposals to the Research Council, they are required to include a DMP, but there is currently no follow-up on quality and implementation. We are working on how to address this, especially now that researchers understand the value of DMPs.

Dedicated funding for open science tasks would be very beneficial. Some researchers still view open science as additional bureaucracy, and there can be a disconnect between open science and researchers’ daily work. We need to demonstrate the advantages and relevance of open science more clearly.

Recognition and rewards are important. At the start, researchers wanted to know what they would receive for their efforts. We awarded certificates for trainers and for completing the nine-month ambassador programme. We also wanted to give them a sign of their ambassador status, but internal bureaucracy has delayed this. Nevertheless, participants gained visibility, and they appreciated small gestures such as homemade cakes and personalised awards.

Reflecting on why we achieved such good results in just nine months, I believe it was due to a clear action plan, a strong team, relevant topics, and an engaged community, all supported by the RCL administration and leadership. We see that an open science culture is beginning to take shape in Lithuania. Researchers themselves are now engaging in constructive dialogue and helping to shape open science policy at the national level. Having RCL experts from different departments was a strategic and crucial step, and the OPUS community has become a key driver of change in open science within the Research Council and across Lithuania.

- Posted In:

- PILOTS ACHIEVEMENTS